Sustainable Urban - Urban Prairie

See You in the Prairie

The DMACC Urban Prairie consists of over 30 native plant gardens scattered across the campus. These plantings offer a glimpse back in time to what Iowa’s landscape looked like just a few hundred years ago. Consisting of a diversity of native plants and grasses, the Urban Prairie not only provides educational opportunities to our campus and community but provides vital ecosystem services as well. Read on to learn more about this unique landscape and how you can enjoy and learn from it.

Native Landscaping

What is a Prairie?

Prairies are specific ecosystems that are part of the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands. They generally have moderate rainfall and a diverse array of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees. The word “prairie” typically refers to the Great Plains of the United States. Prairies contain lush flowers and grasses and rich soil.

Our Prairie Past

The North American prairie lands were formed by the uplift of the Rocky Mountains, creating a rain shadow that resulted in lower precipitation downwind. During the last glacial advance (about 110,000 years ago) and retreat (about 10,000 years ago) most of the material for the prairies was deposited and the terrain leveled.

The tallgrass prairie, one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems in the world, still blanketed our state and much of the Midwest up until just under 200 years ago. Expansive seas of grasses and wildflowers in a mosaic of colors and textures competed for nutrients, water, and sunlight…with some plants growing taller than a horse and rider. Not a single tree was recorded on original land survey maps in some Iowa counties.

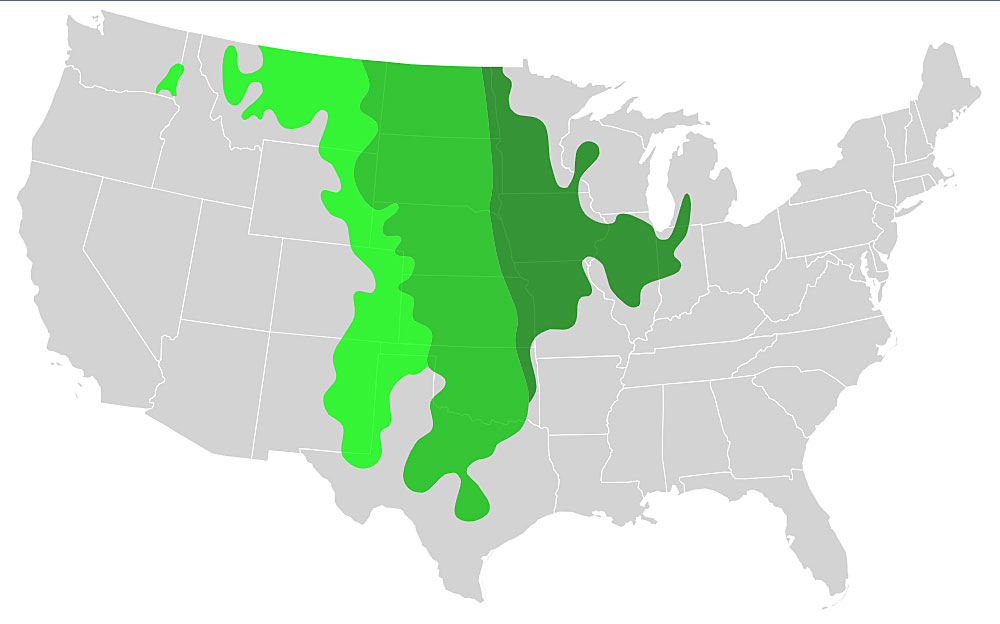

This diverse ecosystem once covered 170 million acres of North America and 14 states in the Midwest, including more than 80% of Iowa.

The tallgrass prairie evolved over millennia to withstand (and require) periodic disturbances including fires and grazing. These disturbances suppressed tree encroachment and created a process for nutrients to be recycled back to the soil.

Fire played an integral role in shaping the prairie and is fundamental to its continuation.

For 10,000-20,000 years, native people lived and subsisted in the prairie lands, using fire for hunting, transportation, and safety. As a natural part of the prairie ecosystem, fire cleared out dead plant material, killing trees but not prairie seeds.

Either set by lightning (about every 5 years) or by Native Americans; fire efficiently replaced nutrients to the soil while restricting tree growth. When fire is not present, trees encroach on the landscape and shade out the prairie plants.

Grazing - For tens of thousands of years, native ungulates such as bison, elk and deer inhabited and shaped the prairie as a considerable portion of the biomass was consumed each year. Animals like bison, elk, deer, rabbits, and grasshoppers feasted on the prairie's diversity, stimulating growth, particularly for grasses. The tender growing points of prairie plants are an inch or so below the ground and thus not injured by fire or gnawing teeth.

The tallgrass prairie is tall! Indian grass, big bluestem, little bluestem and switchgrass all average between 5-6.5 feet, with occasional stalks reaching more than 9 feet. Interspersed was a huge diversity of forbs (flowering plants). Wild indigo, mountain mint, coneflowers, and black-eyed susans, dotting the meadows with blazing color and richness. Each flush of color in a season tended to reach taller than the previous blooming species.

This tapestry of plants and animals supported a wide community of insects, birds, mammals and more. These patterns existed in the prairie for thousands of years and have shaped the selection of plants and animals that have become uniquely adapted to these specific conditions.

Pollinators, like bees and butterflies, played an integral role in the Tallgrass prairie. By spreading pollen between plants, pollinators help the prairie species reproduce and thrive. Prairie flowers and grasses evolved over thousands of years with the insects and birds who pollinate them. Many species of butterfly can only lay their eggs on specific host plants, like the relationship between the monarch butterfly and milkweed.

Tallgrass prairie plants sink their roots deep into the ground (up to 12 feet), providing a strong anchor for the plant, as well as access to moisture in dry times. Despite periodic droughts and floods, the Tallgrass prairie ecosystem suffered little soil erosion and the decomposition of root and plant material created Iowa's legendary black soil.

Cultural Relevance

The archaeological record shows nomadic hunting of megafauna as the main human activity on the prairie for thousands of years. Native peoples would drive bison into fenced pens or off cliffs. The subsequent introduction of the gun, increasing efficiency and killing power, coupled with the indiscriminate killing of megafauna by European settlers lead to the decimation of the bison population. Astonishingly, the bison population plummeted from millions to just a few hundred in about 100 years.

When the first settlers arrived at the tallgrass prairie they called it the “The Great American Desert." Even though the tallgrass prairie had survived and thrived for thousands of years, much of it was lost within 1-2 generations during westward expansion. Nearly all of it disappeared between 1830 and 1900 when Iowa was settled. Marshes and prairie potholes were drained and agricultural development proceeded along the major waterways.

Historical reports describe the sound of the plow slicing through the strong roots of the prairie (invented by Illinois blacksmith, John Deere) sounding like pistol shots. The confined grazing pattern of European cattle and the loss of nitrogen adding animals like bison hastened the prairie's decimation. Today less than 0.1% of the original tallgrass prairie remains in Iowa.

States once covered in a sea of biological diversity are now referred to as the Corn Belt for their highly productive soils and monocultures.

What Remains Today

Historically, prairie covered up to 80 percent of Iowa’s landscape. Now, less than 1/10th of one percent of that original ecosystem remains. These prairie remnants are found mostly in roadsides, utility byways, cemeteries and in state preserves.

What remains of our original prairie exists mostly in roadsides, utility byways, cemeteries and in state preserves.

The tallgrass prairie is and has always been a human-influenced system. We must continue to find ways to connect humans to the prairie for it to survive.

Roadsides, byways, cemetaries, state preserve links:

- Iowa Prairie Resource Center

- Tallgrass Prairie Center - Learn About Your County's Program

- Roadside Prairie: Little Strips of Sustainability

- Hallowed Prairie Article

- Greenwood Cemetery Prairie

- Ames High Prairie State Reserve

Restoration, Research, and Prairie Conservation Strip links:

- Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge - Just outside of Des Moines the NSMWR has reconstructed over 4,000 acres of tallgrass prairie

- Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas

- Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, Illinois

- Konza Prairie Biological Station, Kansas

Native Landscaping

Why is it Important?

Each and every one of us can do our part.

Whether you plant a single pot on your back porch or an entire prairie field, YOU can make a difference! Thanks to information provided by Blank Park Zoo’s Plant.Grow.Fly. program, you will find easy, region-specific garden recipes to help you create a wildlife oasis in your yard. These expertly researched garden recipes will help you to plant flower and grasses that benefit local species the most.

These easy-to-follow recipes can be formed to your landscaping needs, from pet-friendly to sweet smelling, low-budget to no-expenses spared. Gardens can range from several plants in a pot to a whole backyard ecosystem!

Experts agree that even small patches of appropriate habitat on roadsides, in schoolyards, corporate landscapes, and backyards can help support local wildlife like butterflies and bees. These gardens can act as bridges to other gardens; creating a corridor of resources that our native species so desperately need.

Starting Your Garden from the Ground Up

Although the following information is focused on pollinator habitat, native landscaping is reestablishing elements of a historical ecosystem. All prairie animals evolved with these plants. For example, attracting pollinators will attract birds, and so the reconstruction begins!

Find a Location

Consider Your Space - Your garden can be as big as your entire backyard or as small as a single pot. Each garden is important and no effort too small! When using the plant recommendations below, you should favor sunny, wind-sheltered areas. Keep in mind pollinators and their plants need full sunlight for at least six hours per day.

The following list of plants have been formed with the help of the experts at Iowa State University's Reiman Gardens, and support local species. Most of these plants are native to the region, making them low maintenance and better adapted to our climate. The best gardens combine a diversity of plants, encouraging pollinators and other wildlife to spend more time in your garden.

Host plants are the nurseries of your garden, as they are vital in helping pollinator numbers. Butterflies are uniquely connected to their host plants, laying their eggs on or next to specific species of plants. Female adult butterflies lay their eggs on many surfaces of the host plant and generally, in 1 to 2 weeks, a caterpillar emerges from each egg and begins feeding on the plant. Holes in the leaves of your garden are a very good sign: this means caterpillars are present! If you're concerned about the aesthetics of holey leaves, perhaps strategically place the host plants intermixed with nectar plants.

Nectar Plants

Nectar plants will be the source of nutrients and energy for the adult pollinators visiting your garden. These plants will attract all types of pollinators: hummingbirds, butterflies, moths, beetles, wasps, flies, and bees, such as the mason bee and bumblebee. These pollinators will be attracted to many qualities, such as flowers with strong scents, bright colors, and nectar.

Trees & Shrubs

In addition to flowers, trees and shrubs can also serve as both hosts and nectar sources for a variety of butterfly species and will create a multi-layered landscape for a diversity of native wildlife.

Live Outside the Upper Midwest?

Here are your best native plants to include in your garden:

Annuals and Perennial Garden

Border Garden - this garden contains a mix of annual and perennial plants that are easily acquired at most garden centers. Several of the plants are also native to the Midwest. It was designed to be planted against a fence or building, tall plants in the back and plants get shorter towards the front. Make sure to plant in south or west sun for the best success. This would work for a garden that is about 6' x 10'.

Island Garden - This garden plan contains a mix of annual and perennial plants that are easily acquired at most garden centers. Several of the plants are native to the Midwest. It is designed to be planted in the yard so it is visually appealing from all sides. Taller plants are in the center and shorter plants are closer to the edges. Make sure to plant in south or west sun for best success If you prefer to make your Island garden using native plants to the Midwest, it is designed to be planted in the yard so it is visually appealing from all sides. Taller plants are in the center and shorter plants closer to the edges. Make sure to plant in south or west sun for the best success.

Sidewalk Garden

This garden plan contains perennial plants, most of which are native to the Midwest. It is designed to create a narrow border along a sidewalk; it can be used as shown or can be adapted to fit any sidewalk layout. Make sure to plant in south or west sun for the best success.

Butterfly Garden in a Container

This is a simple plan for a butterfly garden in a container or pot. Tall plants are planted in the center and shorter plants planted around the edges. Make sure to place your container in full sun for the best success.

Pollinators also love

- Basking spots. Help butterflies catch some rays by placing large flat rocks and stepping stones in sunny spots so they can perch on them.

- Winter shelter. Some butterflies overwinter rather than migrate. Rather than clearing your garden in the fall, leave it as is until late spring. Eggs, larvae, and pupae may already be present. In the fall you can add crossed logs, standing dry grasses and leaf litter to provide additional overwintering spaces.

- Mineral salts. Creating a mud puddle or a shallow dish filled with sand and water can attract groups of butterflies while providing them with additional nutrients.

Sweet treats. A nectar feeder can also be a great addition to your garden. The recommended solution for nectar is 10 parts water to one part honey. You can also add treats of overripe fruit, such as bananas, pears, plums, apricots, peaches, watermelon, cantaloupe, and grapes.

Butterflies and many birds are attracted to large splashes of color in the landscape. Planting in groupings of 3-5 of the same plant is important when creating these color splashes. Add plants of different heights, creating tiers within your landscaping.

Seeds or Starter Plants?

Using potted or starter plants may be the easiest choice for small garden areas or beginner gardeners, as the plants are already established and are lower maintenance to keep alive. However, for larger areas, more advanced gardeners, and those with lower budgets, seeds can also be a good option. Read on for more information about both approaches.

- Ambitious seed starters should start their seeds indoors as early as March or April (or earlier). Keep in mind each plant is different, so consult your local greenhouse or use the instructions printed on the seed packet to know the ideal time to start each seed. To start your seeds, you'll need plastic flats, a good soil mix (suitable for seedlings), a natural light source, and moisture from either humidity or watering. Generally, allow your seeds 4-8 weeks of growing time indoors before transplanting outdoors after the risk of frost has passed.

- If sowing seeds directly into the ground, you will first need to prepare your soil in early spring. Clear your garden of weeds and debris, then cultivate or till the soil to a fine consistency. It's best to work the soil when it has had time to dry out, as soil tends to clump when worked while still moist. After the danger of frost has passed, you can sow seeds in your garden about 1/4-inch deep and 12–18 inches apart. Seed mixes may also be used and may be more cost effective in larger areas. When using seeds, remember that plants need time to mature. You may not have mature flowering plants until the following growing season.

If using potted plants, plan your garden and prepare the bed before purchasing plants. Once you have purchased your plants, keep them well watered prior to planting. When you're ready to plant, dig a hole as deep and as wide as the pot the plant came in. Drop the plant in the hole and fill in soil as needed. Provide deep watering while the plants become established. The idea behind deep watering is to let the water soak deeply into the soil and then not to water for several days. Deep watering, followed by a lack of water in the soil near the surface, encourages roots to go deeper into the soil, enabling the plant to draw moisture from the soil more readily.

Make informed decisions on what you're buying and where it came from. Ask your greenhouse or nursery if their plants are grown locally. Native cultivars are preferred. One of the most important questions to ask is if herbicides or pesticides were used when growing the plants. We want to provide a safe place for the pollinators to reproduce and collect nutrients.